Mugabe and the White African raises all kinds of questions. If you are white, can you be African? Do white African farmers today owe black Africans anything because of the transgressions of European colonists from 100 years ago? If so, should there be a forced transfer of land ownership from whites to blacks if the land is then left uncultivated and barren?

Mugabe and the White African raises all kinds of questions. If you are white, can you be African? Do white African farmers today owe black Africans anything because of the transgressions of European colonists from 100 years ago? If so, should there be a forced transfer of land ownership from whites to blacks if the land is then left uncultivated and barren?

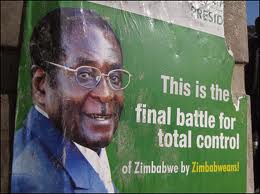

The film focuses on the land reform policies of Zimbabwe’s longtime president, Robert Mugabe. On one side are white farmers like Mike Campbell and Ben Freeth, who believe they have rightful ownership to their land. On the other side is Mugabe and many black Zimbabweans who argue that the land was originally owned by blacks before being grabbed by white colonists, and so it should be returned to the proper owners.

The real reasons for Mugabe’s interest in forcibly transferring land from whites to blacks are probably much more cynical than moral or legal. Namely, it allows him to deliver favors to loyal cronies and consolidate his power. And those cronies are most definitely not farmers. As a result, the land goes to waste, and a country that was once considered the “breadbasket of Africa” now must receive massive international food aid.

Regardless of whether you feel Mike Campbell and his family owe anything to their black countrymen, there is no disputing that he was (he died in 2011) one brave chap who believed in his right to the land. He and Freeth run the farm jointly. Marauding gangs constantly threaten them with violence if they don’t relinquish the farm, but they stubbornly refuse. And they defend their farm entirely by themselves. In a country experiencing total lawlessness – Freeth compares it to the chaos of “a game with absolutely no rules” – they can’t rely on a justice system to intercede.

The violence escalates when some of their farm workers are attacked and beaten. Campbell and Freeth seek out the help of an external judicial body, the Southern African Development Community tribunal to have their case heard. The court repeatedly delays making a decision, and, in the meantime, the families’ safety becomes more dire, as several of their farm workers are attacked and beaten. The violence eventually climaxes shortly before the court eventually comes to a decision.

The decisions by tribunals or the philosophical/legal debates over land ownership rights are all moot in the face of one indisputable fact that the film makes clear: all humans, by their nature, are tribal. “Go home to Europe! You don’t belong here!” a black Zimbabwean shouts at Campbell…not much different than some of the sentiment that surrounds the anti-immigration policies in Europe and the U.S.