Restrepo is a documentary film that all non-military civilians ought to see. We often hear commentary about the divide that exists between those serving and those who don’t; we civilians cannot understand the experience of soldiers serving in America’s recent wars, nor can they explain it. A 90-minute film can’t fully depict the life of a soldier in Afghanistan, of course, but watching Restrepo makes you appreciate far more the sacrifices and dangers that America’s soldiers volunteer for.

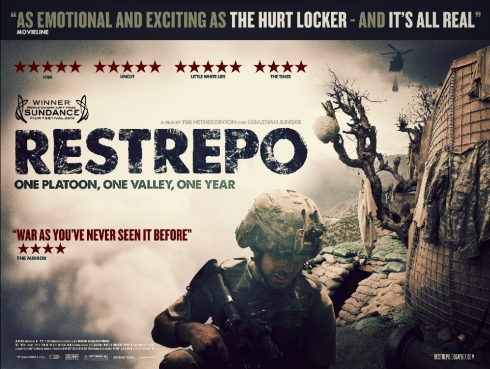

The film is an extraordinary glimpse into the life of the Second Platoon as they attempted to gain control over the Korengal Valley in eastern Afghanistan, an unruly territory that has resisted past American efforts to control it. Filmmakers Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington were embedded with the platoon as it advanced from “Outpost (OP) Kop” further into the valley to set up “OP Restrepo.” OP Restrepo is named after Juan Restrepo, a member of the platoon who was killed soon after arriving in Afghanistan.

Much of the film feels like a study in contrasts. The most obvious one is a contrast of cultures. Young American men, armored to the nines with helmets, bullet-proof vests and machine guns, pass through the impoverished shepherd villages of wizened old men, women and children. The soldiers obviously do their best to be respectful, but when they patrol a village in the aftermath of a bombing mission, bust down doors, and encounter dazed, frightened villagers, it’s hard to imagine that there’s much possibility for connection.

Even so, the soldiers and their leaders do seem well-intentioned. A sergeant talks to the village elders about bringing in new roads and new jobs to the valley, but all that seems awfully grandiose considering the circumstances. It’s hard to know exactly what the villagers want. They mainly seem worried about avoiding trouble with the Taliban, finding out why one of their young men has been detained by the army, and getting compensated for the cow the Americans killed.

The easy thing would be to watch a film like Restrepo and point fingers at the foreign invaders. But seeing the soldiers wrestle or dance with each other, sunbathe, play guitar, or reminisce about their lost buddy Restrepo makes them all very human and likeable. And it’s painful to see one of the soldiers lose control on a mission when his close friend is shot and killed. “Don’t look at him,” is the best advice a comrade can offer as a tarp is pulled over the fallen soldier in the frenzy of combat.

Observing moments like this, hearing the soldiers talk candidly about their fear of going into battle, and also seeing occasional moments of bloodlust is powerful and frightening evidence of the effects of war. All the soldiers speak candidly about the psychological damage they have experienced, and the naive among us wonder: couldn’t all this be avoided if each side had the chance to have a little wrestle and then dance together?